For the last time, Stepdad beat up Mom and Sean Wolfe, then 14, and was hauled away in handcuffs.

“It finally snapped,” Sean says on a Virginia Beach Potter’s House podcast. “We were done. A restraining order was put. We finally got away from him and he never came back. My mom had to work three jobs after that.”

Sean’s stepdad was violent drug and alcohol abuser, along with his wife and son, until he got scared off by the restraining order and moved away.

The legacy the stepdad left his son was to be a “really angry guy. I didn’t have a lot of friends because I had a bad temper. I was very sensitive and didn’t know how to process. I nurtured a hatred for myself, and through that I hated everybody else.”

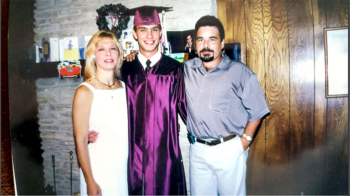

He liked playing the trumpet in high school and learned Mariachi music. As soon as he graduated from high school, he joined the Air Force to get away from Round Rock, Texas.

His grandmother was always praying for him, and his biological dad wound up getting saved and also started praying.

Sean got stationed in Pensacola, FL, and enjoyed the weekends on the boardwalk drinking, despite being underage.

“What do military guys do when they go drinking? They go get tattoos,” he says. While his buddy got a Chicago Bulls logo on his shoulder, Sean was planning a Celtic cross on his back with a rose vine memorializing the members of his family.

“I must have been really drunk,” he says. “I was this white guy who thought he was Latino because he knew how to dance Mexican folkloric dance.”

He was to bring the first installment ($400) next Saturday. Along with seven guys in one car, he was set to go, just when his grandmother called on the barracks phone (before the time of cell phones). Sean was trying to hang up politely because his buddies were hurrying.

“Sean, don’t do something you’re going to regret for the rest of your life,” Grandmother ominously told him. The timing was unnerving. But Sean brushed that off. “I love you, Grandma. Bye,” he said.

Then his dad called on the barracks phone. “Son you’ve been on my mind. Sean, I don’t want you to do something that you will regret for the rest of your life.”

Sean dropped the phone.

He recovered himself and hung up.

By the time he caught up with the guys, they had left him.

Sean was furious. But he couldn’t afford the $80 taxi fare to catch up with his friends. So he went to the gym and the theater and fumed until it was 8:30 p.m.

That’s when his commander showed up with military police. Bam, bam, bam, they pounded at the door. Sean answered and was quite surprised.

He had to report to the office. Waiting for him inside were a major, a lieutenant, a senior sergeant, police officers and a detective. “Where were you today?” he was asked.

Sean rattled off his day, all on base. They asked for the movie ticket stub, which after running to his barracks, he produced.

“Ok, he checks out,” one said. “We asked to verify you weren’t at the beach today.”

The other seven airmen had been drinking and had gotten into a fight; two were in jail.

“If I had gone, assuredly I would have had an Article 15 (commander administered disciplinary action) or maybe even completely kicked out with my past disciplinary actions,” Sean says. “Everybody knew we were running buddies, all doing the same thing.”

The two guys got court-martialed; the others got Articles 15.

At his last supper on the Boardwalk in 1999, some teenagers witnessed to him. “We want to say Jesus loves you and you can be born-again. Would you like to do that?”

“Get the F out of my face,” Sean responded.

“I was so mean to those guys.”

Sean was transferred to Cannon Air Force Base in Clovis, New Mexico, “the armpit of the Air Force,” Sean calls it. As he drove around endless pastures with no hustle and bustle, he realized, “I’ve died and gone to Hell.”

It was his tech sergeant Jack Evans who talked to Sean about Jesus one winter day. “It was bitterly cold. It’s 20 degrees and the wind is blowing 30 mph, so there’s a windchill factor,” Sean remembers.

He was on the flight line doing a repair on an F-16, when his hand slipped and his body slammed into the bulkhead. Like most military guys, Sean let out a string of profanities.

“Wolfe, you need to watch your mouth,” Sgt Evans told him.

“F— off!” Sean responded before he could think.

“I’m a two-striper telling a six striper to F— off,” he recalls. “That’s all I need.”

“I’m a two-striper telling a six striper to F— off,” he recalls. “That’s all I need.”

Surely, he would get another Article 15 discipline.

But Sgt. Evans looked at him in love. “Wolfe you got a really big chip on your shoulder. Tell you what, if you come to church with me, I may forget this ever happened.”

Sean had no desire to go to church, but his desire to avoid another Article 15 was greater, so he accepted.

“You’re on!” he responded and thought to himself: I’ll grin and bear a little church service.

“I used to go to church services in high school for girls or for drug deals or for anything but the right reason,” he explains.

To ward off church goers who might want to talk to him that Sunday, Sean had smoked a particularly pungent-smelling cigar beforehand to create a barrier between him and the church members. He called it a “smoke screen.”

After being greeted friendly, he sat with Sgt. Evan’s family. As the sermon got underway, Sean was impressed with the passionate presentation: Man this guy really believes what he’s saying, he thought.

At the end of the sermon, there was an altar call, and Sean passed. After the call to salvation, there was a call for Christians to also go up to the altar to deal with sin.

This surprised Sean.

“All these people go to the altar. I was really perplexed,” Sean says. Why would they go to the altar if they already had accepted Jesus? “It hit me so hard between the eyes. No way! These people can’t be serious!”

It was a stark contrast to his own personal “turmoil, violence and abandonment,” the legacy of his childhood that continued to play out in his mind and deprive him of restful sleep, he says.

“I was struck by it, captivated by it,” he remembers. “It spoke volumes that they did what they said they would do.”

“Wolfe,” Sgt. Evans turned to him. “Are you ready to get that chip off your shoulder.”

“I don’t want to lie anymore,” Sean responded.

He relented and went to the altar to accept Jesus, which seemed anticlimactic. There was no weeping, no choirs of angels singing, no thunder from Heaven.

“That’s it?” Sean asked Sgt. Evans.

“If you meant it, you’ll know,” Sgt. Evans responded.

Sean still just wanted to get back to the barracks, but church members invited him over for a “home cooked meal,” which he couldn’t resist after so much military chow. People kept loving on him and being interested.

Finally, when he was returning to the base, he pulled out a cigar as was his custom. But he paused and pondered what was going on inside. Strangely, he no longer had the desire to smoke.

“I haven’t been tempted to smoke since,” he says.

He dumped $80 of smoking paraphernalia in the dumpster behind the church.

He went home and slept like a baby for the first time ever.

Previously, “I had nightmares,” he explains. “I’d wake up all the time, fear of being hurt or abandoned or threatened. I was just a scared little boy. It was those terrors in the night.”

Smoke breaks at work turned into coke breaks. He never missed a service or Bible study.

“I began making friends,” he says. “I was afraid to do that. I had fake friends in the military. We hooked up in the Air Force because we could outnumber the Marines and wouldn’t get beat up. They welcomed and embraced me in.”

Today Sean is a pastor in Hope Mills, North Carolina.

If you want to know more about a personal relationship with God, go here

About the writer of this article: Pastor Michael Ashcraft is also a financial professional in California.