When 11-year-old Vernon Turner caught Mom in the bathroom about to shoot up heroin one day after coming home from school, she calmly told him sit down and watch.

“I want you to see me do this because I don’t ever want you to do this,” she said, “because this is going to kill me.”

The stupefied boy responded: “If you know it’s gonna kill you, why do you keep doing it?”

As she tied the thin rubber band around her arm and inserted the syringe into her vein, she explained how she had been gang-raped at 18. She took heroin, she said, “to not remember, to take away the pain.”

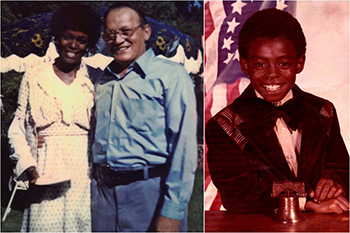

As a teen, mom lit up a room with her smile. She was a track star, a flag girl and a baton twirler.

As a teen, mom lit up a room with her smile. She was a track star, a flag girl and a baton twirler.

But her youthful innocence died one afternoon in Brooklyn on her way home when two men grabbed her, violently hauled her to a rooftop, where they covered her mouth and took turns on her with another man. They only spared her life because they heard someone coming and scattered quickly, Vernon explains in a 2016 online “letter to his younger self.”

Overcome by fear, shame and confusion, Mom never reported the rape. When a few weeks later she found out she was pregnant, she decided against abortion.

The baby boy — product of that murderous aggression — was Vernon.

“Mom loves you, Vernon. But you remind her,” she told him. “No matter what she does to forget about what those men did to her. There you are, in her own home, every day … reminding her.”

“Mom loves you, Vernon. But you remind her,” she told him. “No matter what she does to forget about what those men did to her. There you are, in her own home, every day … reminding her.”

Mom slurred on about how she had turned to prostitution to feed her dope habit. Eventually, she had met an Italian New Yorker who took her in to his home on Staten Island and gave her four more children but mistreated her.

Vernon was stunned by these revelations. He had known about the drug use, but he hadn’t known about the other harsh realities.

Four years later, his mother was dying, and Vernon actually prayed that she would die — so he could get on with his life and salvage some semblance of a childhood.

Because mom was always “sick,” he had to cook dinner, braid hair and change the diapers. mom and dad always argued. All the time, she was either on drugs, out searching for her next fix or stuck in an unconscious lull between highs. When she looked at Vernon, it was as if she looked right through him, as if he were invisible.

Because mom was always “sick,” he had to cook dinner, braid hair and change the diapers. mom and dad always argued. All the time, she was either on drugs, out searching for her next fix or stuck in an unconscious lull between highs. When she looked at Vernon, it was as if she looked right through him, as if he were invisible.

So he bent down at his bedside and prayed that the nightmare could be over.

Then she died.

After a life of drugged-out and drugged-starved “sickness,” she caught a real sickness, pneumonia, which swiped away what was left of her life within three days.

Vernon was pierced with guilt over his unrighteous prayer and his simmering anger at mom. He talked to the casket at the gravesite for a full hour, after all the funeral attendants had left, keeping burial workers at bay.

Vernon was pierced with guilt over his unrighteous prayer and his simmering anger at mom. He talked to the casket at the gravesite for a full hour, after all the funeral attendants had left, keeping burial workers at bay.

He told her he was sorry, that he didn’t really want her to die, that he missed her. He regretted that prayer for the rest of his life.

But he didn’t resign his life to self-destruction.

Out of the shameful misery of brokenness, Vernon rose to excellence because of one thing: football.

Ever since he stepdad took him to watch the Giants play the Bears in a preseason NFL game, Vernon loved the pigskin — and it gave him a motivation in life. It was an outlet for anger and vexation.

At 98 pounds, he was a twig of a freshman, so he hid weights under his clothes to weigh in for tryouts. Coach didn’t fall for the ruse but took him on the freshman team because he saw his spirit. He was on the varsity team by his sophomore year. He threw 4,000 yards during his senior year and won All-State honors.

At 98 pounds, he was a twig of a freshman, so he hid weights under his clothes to weigh in for tryouts. Coach didn’t fall for the ruse but took him on the freshman team because he saw his spirit. He was on the varsity team by his sophomore year. He threw 4,000 yards during his senior year and won All-State honors.

He wasn’t highly recruited and wound up at a Div. 2 college team. His stepdad died during his freshman year. Suddenly, he was responsible for his siblings. He flew back from college and cajoled his aunt in Brooklyn to move to Staten Island to raise his siblings while he continued college.

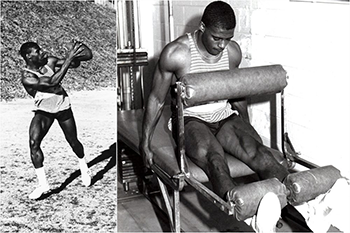

The only way to provide for his brothers and sisters, he decided, was through a professional football career. Coaches mocked his aspirations because he was small-framed. But this only made him more determined to triumph: he woke up at 2:00 a.m. to run his own training program.

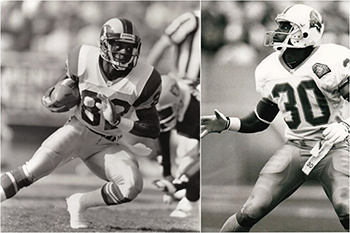

The hard work paid off. Vernon played, starting in 1990, for the Denver Broncos, the Buffalo Bills, the LA Rams, the Detroit Lions and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. He played mostly running back and kickoff return. He retired after eight years in the NFL.

“I had no business playing in the National Football League. I was not that good. If it weren’t for the fact that my mom passed when I was sophomore in high school and my dad passed when I was a freshman in college…I shifted to a survival mode,” Vernon says.

“I went to training regiments from hell through college. Half the time I was crying for the pain in my body, the other half of the time I was crying because if I didn’t pull this off, it was the only thing that would keep my family together. When I got into the National Football League, I went back home and I cried with my family because I kept my family together, I kept the roof over their heads.”

Vernon admits he feels shame and regret over his birth and his treatment of his mom. But as the bad things have turned to good, Vernon now thanks God that his mom didn’t abort him. His website includes a music video that asks why bad things happen to good people and encourages them to trust in God’s plan.

“Back in 1966 she made an unbelievable sacrifice to keep me. Nobody would have faulted her for aborting me,” Vernon says. “Nobody would have faulted her giving me up for adoption. The sacrifice that that woman made for me… My goal and mission in life is to leave a legacy that she would look down and be proud of me now.”

Michael Ashcraft pastors the Lighthouse Church of Van Nuys.

Great Story, God has plans for all of us, amen

Comments are closed.