By Brian Nixon —

While waiting in Albuquerque, New Mexico’s airport—on my way to Northern California—I had a couple of thoughts on my mind. One, to finish the flight. Being a sardine in a can, cramped at 30,000 feet, is not my idea of fun.

The other thought: Upon touchdown, to take in the Strentzel—Muir home slowly.

Growing up in both New Mexico and California, John Muir was a household name, at least in our family. His impact upon California is renowned and well-documented in books, film, and eponym’s. And though lesser known, Muir’s visit to New Mexico caused him to write a friend that New Mexico is “a land of surpassing loveliness and strangeness.”

Muir’s influence in both states looms large, particularly as the patron saint of environmental causes. As an inhabitant of both states it’s been an aspiration of mine to visit his home. After touching down in Oakland, California, along with my wife and her brother and sister-in-law, we head to the John Muir home in Martinez, California, a National Park.

As hoped, we peruse the site slowly, meeting up with my wife’s other brother. As a band of pilgrims, we embark on a tour as light rain falls. Though I wouldn’t call the sojourn a religious pilgrimage, per-se, but something more akin to a literary pilgrimage, our intent was similar: a journey to seek a deeper understanding of the man and his mission.

Sitting on top of a small hill, surrounded by trees, orchids, and lawn, the white “Big house” as Muir liked to say, was built in 1882 by Muir’s wife, Louisa Wanda Strentzel. As a 17-room Victorian home, the building is lovely, both inside and out, and must have been a marvelous retreat before the clamor of the Bay Area infringed upon the town.

Of all the spaces at the Muir home, I was attracted to the writing room, what Muir called the “Scribble Den.” In the room, one finds his original writing desk, period chairs, furniture, a clock, papers on the floor, books on shelves, and an Oliver typewriter (which, to my knowledge, I don’t think Muir used). Per the US Park Service, “Muir converted one of the bedrooms into his private retreat…. Here, at his desk, Muir wrote, and consolidated his well-renowned reputation as a preservationist, founder of the Sierra Club, and great friend to Yosemite and other national parks.”

Walking to the top level of the home to ring the bell, I stopped to read some quotes, two of which caught my attention and caused me to connect Muir to another notable Scotsman.

The first quote concerns beauty: “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play and pray in, where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike.”

The other citation was on the topic of tea: “As to tea, there are but two kinds, weak and strong, the stronger the better.”

As a lover of tea and beauty, particularly in nature and art, both quotes resonated with me.

However, as stated, the quotes drew my mind to another Scotsman, George MacDonald,

whom I happened to be reading before leaving for California.

Concerning the topic of beauty, MacDonald begins his poem, “I Know What Beauty Is” with these words:

“I know what beauty is, for You have set the world within my heart.” MacDonald continues the poem with admiration for natural and spiritual beauty.

The second quote is from MacDonald’s novel, Thomas Wingfold, Curate, where George, recommends to Helen, his cousin, “A cup of tea and a little Beethoven!”

The later quote reminds me of MacDonald’s literary champion, C.S. Lewis. Though connecting tea to books (and not music), Lewis’ famous tea quote is “You can’t get a cup of tea big enough or a book long enough to suit me.”

As fun as the quotes are, the comparison between Muir and MacDonald goes far beyond simple adages.

Here’s some similarities to consider:

- As noted, both were born in the Eastern section in Scotland. MacDonald in Huntly (northwest of Aberdeen) in 1824, and Muir in Dunbar (due East of Edinburg) in 1838, roughly a four-hour train ride from one another.

- Both were raised in rigid Christian households. For MacDonald, it was Congregational Calvinism; for Muir, his father was a devoted follower of Thomas and Alexander Campbell, the founders of the Restorationist Movement which spawned several denominations including the Church of Christ and the Disciples of Christ. It’s because of the Campbell’s influence that Daniel Muir, John’s father, moved the Muir family to the United States.

- Both left their birth denomination to find a differing expressions of the Christian faith. For MacDonald, he joined the Anglican church. Muir did not join a denomination in the US but found God in the temples of nature. According to Muir scholar, Frederick Turner (Rediscovering America), “Muir was first and forever a Christian even if the faith was uncomfortable in places and had to be adjusted to fit his own spiritual needs.” However, Muir is recognized as a “holy man” within the Episcopal church, with his minor feast day falling on April 22nd.

- Both were writers. MacDonald wrote over 50 books—novels, poetry, plays, and short stories. Muir wrote roughly twelve books and over 300 articles.

- Both valued nature as a spiritual practice. Though not pantheists (God in being, and being in God), they found spiritual solace in nature, seeing creation as God’s thoughts made visible, great gifts to enjoy and protect.

- Both MacDonald and Muir had deep, personal heartache. In his life, George MacDonald buried four of his eleven children, Lilia, Mary, and Caroline, and Maurice. For Muir, his personal heartache came from an accident that damaged his eye, what the Natural Parks state as an injury “that changed his life.” And more importantly to Muir, the lost battle over the damming of Hetch Hetchy, ruining pristine nature in the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

- Both were theopoets, combining faith with imagination. Their creative words stand the test of time. As the American Writers Museum notes of Muir, “Muir’s writing is lyrical and energetic, with a hunger for authenticity.” Concerning MacDonald, C.S. Lewis writes, “My own debt to this book [Phantastes] is almost as great as one man can owe to another,” concluding, “That night my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptized.”

- Both men travelled throughout the United States. Though Muir became a naturalized citizen, he traveled widely—by foot and train—throughout much of the US. MacDonald did a speaking tour of the US, lecturing at various colleges, churches, and literary events on figures such as Robert Burns, William Shakespeare, and John Milton. During his travels, MacDonald connected with many notable people, including Mark Twain.

- Both men related to the work of essayist, poet, and minister, Ralph Waldo Emerson, meeting him at differing times in their US travels. Muir met Emerson in California; MacDonald met Emerson on his literary tour.

- MacDonald and Muir were inspired by the artwork of British-American painter Thomas Moran, a member of the Hudson River School of artists. MacDonald’s poem The Haunted House was influenced by a painting of Moran of an abandoned home. In turn, Moran was inspired by Muir’s dedication to nature, painting a landscape of Hetch Hetchy from a sketch by John Muir and an etching entitled For Picturesque California, John Muir, 1888. Muir and Moran met briefly on a couple of occasions, swapping notes on the state of the American wilderness.

- Both men are considered Christian mystics. Orbis Books published a work on Muir’s religious writings entitled, John Muir: Spiritual Writings. And many books have been published concerning MacDonald’s theological and Christian views, including The Harmony Within: The Spiritual Vision of George MacDonald by Rolland Hein.

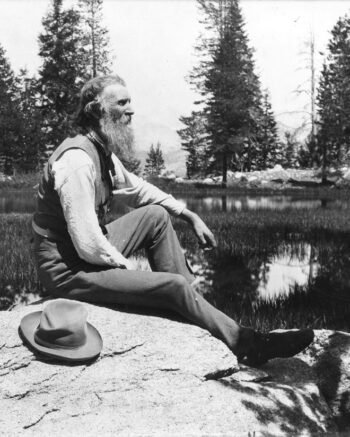

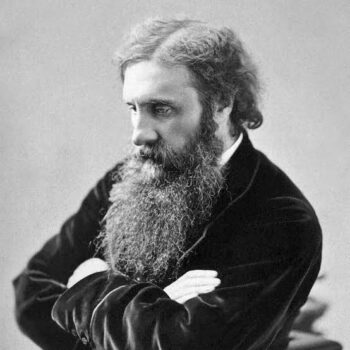

- Finally, both men had mighty beards. As photos attest, it seems like the Scottish Highlands left an indelible impact upon their personal appearance, fitting for the time.

Comparison could continue, but I’ll stop—for now. If one thing is certain about MacDonald and Muir it’s this: they recorded the truth, beauty, and goodness of God in unique ways. Muir championed God’s creation, preserving, and protecting it; MacDonald championed Christ-like living and creative pursuits, finding God’s love manifest in manifold ways.

A tour of Muir’s home only provides a small snapshot of the man, as would a tour of one of MacDonald’s many dwelling places. To understand more about the men, I encourage you to read their works and books about them. I’d start with the following two biographies:

- George MacDonald: Victorian Mythmaker by Rolland Hein. And for a short timeline, Wheaton College has marvelous information, found here: https://www.wheaton.edu/academics/academic-centers/wadecenter/authors/george-macdonald/.

- A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir by Donald Worster. For quick information, go to the National Parks Service website, found here: https://www.nps.gov/articles/john-muir.htm.