By Michael Ashcraft —

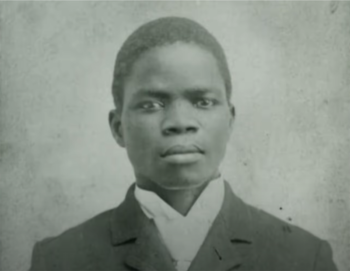

When a light flashed around him and his bonds fell off miraculously, Prince Kaboo heard a voice to run from his captors, the warring Grebo tribe on the coast of Liberia.

So when he wandered into church on a coffee plantation and heard the story of Paul’s conversion on the Damascus Road, he burst out: “That happened to me!” and began to share about his daring escape, his wanderings through the jungle and his coming to Monrovia, according to a Vision Video.

It was his first time in a church, so he didn’t know to keep quiet. But he was thunderstruck by the obvious parallels and was overcome with wonder. He immediately became a believer in Jesus Christ.

Ultimately, Kaboo — renamed Samuel Morris — became essentially a missionary to America. At a time when African missionaries are emerging as God’s antidote for “post Christian” Europe, Kaboo was a forerunner for this reversal of roles, when developing countries bring renewal and revival to First World nations.

For years in Monrovia, Kaboo painted houses to make money while he learned to read and was instructed in the principles of Christianity from his tutor, missionary Lizzie MacNeil. The former son of the village chieftan immediately consulted his Father in prayer for everything and had a voracious appetite to learn more about the Holy Spirit.

One day, Lizzie teasingly informed him that she possessed nothing further to teach him about the Holy Spirit and that if he wanted to know more, he would have to go to New York and learn from her mentor, Stephen Merritt.

It was a joke, but Kaboo took her seriously. As soon as it was said, Kaboo concluded he needed to go. So he planted himself on the shore near the place he expected to confront the captain of a 300-ton trading vessel in port, a ship he found out was headed for New York.

“My Father tells me that you’re supposed to take me to New York City,” Kaboo told the surprised captain.

The captain, a rough and gruff seaman, however, had no time for idle talk and nonsensical freeloaders, so he kicked him aside.

Kaboo stayed on the beach for the remainder of the days the boat was in port. When it was about to embark, the captain discovered that some of his crew had abandoned ship, so he decided to take Kaboo on as part of the crew, assuming he knew the intricacies of rigging because he belonged to a tribe that often supplied crewmen.

Kaboo had no seafaring experience whatsoever, and when he climbed the rigging to trim the sails, he was absolutely terrified as the masts, 100 feet in the air, pitched from side to side and nearly touched the surface of the stormy seas.

Seeing his evident terror, the cabin boy, who wanted to graduate to sailor, proposed they switch jobs. But nobody consulted the captain, so when Kaboo showed up to attend the cabin, the captain grew furious and rose to beat him.

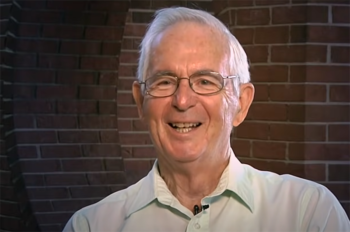

“All Morris knew to do was to fall on his knees and pray for God to calm the heart of this angry man,” says Charles Kirkpatrick, professor emeritus at Taylor University. “When he saw that boy kneeling in prayer, the captain was moved to recall the days when he had grown up on a farm in New Jersey in Christian home and had been taught the scriptures and how to pray by his mother.”

Over the next few days, the captain’s heart softened. He asked Kaboo about God and became a believer. He was Kaboo’s first convert from America.

After the captain, Kaboo turned his attention to the crew. Sailors at the time were picked up and dropped off in any port around the world. They were often dagger-wielding brigands closely resembling outright pirates. On Kaboo’s ship there was a Malay who had an unbearable temper and threatened people at will.

On a certain occasion, the Malay moved in to slash a fellow sailor. While others stepped back, Kaboo stepped in between the attacker and his victim and boldly told him to put away his dagger.

“The Malay didn’t like that interference and was about ready to use the sword on Morris,” Kirkpatrick says. “But his arm was seized and he could not bring it down. The captain witnessed that and realized that something truly miraculous had occurred in their midst. The result of that incident was that several people trusted in Morris’s God and became believers as well.

“By the time the journey was over about half of the crew became believers,” he adds.

When they sailed under the newly-constructed Brooklyn Bridge, Samuel — the missionary-given name he now used — embarked immediately to find Stephen Merrit among New York’s two million inhabitants.

The first person he asked, probably a vagrant, just happened to know him and offered to take Samuel to his mission eight blocks away.

“That this one person would happen to know Stephen Merrit is part of the miraculous nature of the story,” Kirkpatrick says.

Merrit told him to wait for him in the mission while he went to a prayer meeting and forgot him until hours later. When he sought Samuel at the mission, he found the young African had already converted 17 men in the mission to Jesus.

Merrit invited Samuel to live at his house.

One day he dropped Samuel off at Sunday School. “The altar was full of young people, weeping and sobbing,” Merrit found, when he returned for him.” I never found out what Samuel said, but the presence and the power of the Holy Spirit were so present that the entire place was filled with His glory.”

Almost immediately, the youth in Sunday school formed a missionary society to pledge support to Samuel. Everywhere he went he wowed people with his simple faith and boundless fervor for the Lord.

Samuel wasn’t interested in the tall buildings of New York. He had come to learn from Merrit about the Holy Spirit, but instead Merrit says he learned from Samuel.

Merrit sent him to Taylor University in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The university was on the verge of bankruptcy following the Civil War. University president Thadeus Reed enthusiastically received the young African on scholarship.

The school was overrun with rationalism and philosophy more than with evangelical Christianity.

“They were more into Aristotle, Socrates and Plato than they were to the New Testament,” says Jay Kesler, president emeritus of Taylor University. “But he brought this new interpretation to biblical faith so that many kids were converted. They were saved.”

“Morris’s coming to campus brought revival to the place,” Kirkpatrick says. “He brought a spiritual awakening to the student body.”

His insights into scripture astounded his professors. He had a reputation for loud and long prayers in the dormitory, which annoyed fellow students at first but eventually drew them into a deeper relationship with God. He received invitations to share at churches around town. Everybody who heard him were thunderstruck by his anointing. He brought revival to the churches.

After his training in the U.S, the plan was for Samuel to return to Liberia and evangelize his fellow tribes.

But it was not to be. On a cold January night during his second winter, Samuel was determined to attend a prayer meeting at a nearby church. He wasn’t adequately dressed for the zero-degree weather and caught pneumonia. He died in May of 1893.

“The shock to the campus was enormous. The whole city of Fort Wayne knew of this young man by then,” Kirkpatrick says. “The African-American community, of course, was stunned because he had become their hero. The funeral was one of the largest the city had ever seen at that time, and maybe since. Carriages wound their way for miles back toward the campus.”

By then, Taylor University had turned the corner financially. They moved to Upland where they were offered tax breaks. Though shocked, his admirers sold hundreds of thousands of copies of booklets about his life, the funds from which saved the university economically.

“Two hundred and forty thousand copies sold brought in probably around the equivalent of $5 million,” says Kesler. “Most people of that era credit that story with putting Taylor on the map.

Samuel never went to Africa as a missionary.

“But the way he died and the type of individual he was drew a lot of people to sign up for ministry or go as missionaries overseas,” says Elijah Tarpeh, president of the Sinoe County Association in the Americas.”

“The number of people who left Taylor University to go to the mission field is really large,” says Kesler.

If you want to know more about a personal relationship with God, go here

Michael Ashcraft was a missionary in Guatemala. Now, he writes for God Reports and helps people with life insurance and annuities as a Christian financial professional in California.

[…] One day he dropped Samuel off at Sunday School. “The altar was full of young people, weeping and sobbing,” Merrit found, when he returned for him.” I never found out what Samuel said, but the presence and the power of the Holy Spirit were so present that the entire place was filled with His glory.” Read the rest: African missionary to America Samuel Morris […]

Comments are closed.