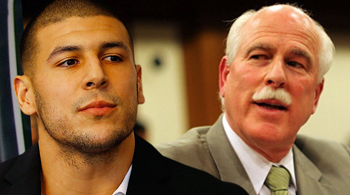

Before ex-Patriots star Aaron Hernandez hung himself in his jail cell, the sheriff was reaching out to him with the gospel.

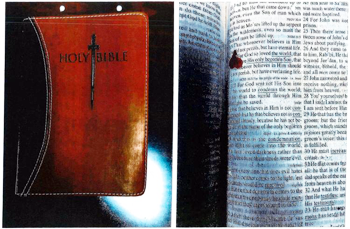

“I did read the Bible,” the New England All-Pro tight end told Sheriff Thomas Hodgson, according James Patterson’s All American Murder excerpted in the New York Post. “The weirdest thing happened: I opened it, randomly, and it was all about me,” he said.

But before long, Hernandez’s defense team got wind of the growing closeness between their client and the sheriff — and they demanded a transfer to another jail. They didn’t want any ‘fraternizing with the enemy’ during the ongoing trial.

Sheriff Hodgson, a grandstanding God-fearing American, who styles himself after Joe Arpaio, wasn’t fishing for evidence but for souls. A zealous Christian, Hodgson believed that a high profile story of redemption would teach the nation’s youth the dangers of sin and the power of God’s forgiveness. But, after 18 months of chatting him up about the Bible, his progress got cut short.

When Hernandez, at age 27, was found suspended by a bed sheet noosed around his neck and tied to the window at 3:00 a.m. on April 19, 2017, he had written John 3:16 on his forehead. His Bible was open to the same passage. He was rushed to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead an hour later.

Hernandez’ meteoric rise to the top NFL team and his tragic demise following the murder of his fiancée’s sister’s boyfriend is a story of the hollowness of the American Dream without God.

Hernandez’ meteoric rise to the top NFL team and his tragic demise following the murder of his fiancée’s sister’s boyfriend is a story of the hollowness of the American Dream without God.

Hernandez was an anomaly in football. While street toughs abound in the bruising sport, most of them leave the streets behind when they enter the glory of the gridiron. They have traded up for the trappings of wealth and fame.

But Hernandez didn’t transition. He had a 7,100-square-foot house and a $40 million contract, but he stayed loyal to his “hood” and thug life.

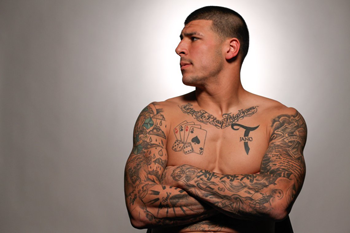

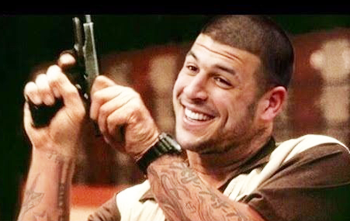

Hernandez relished violence and feared nothing. Together with Rob Gronkowski, they formed the most feared pair of tight ends in the NFL. While Gronk offered some of the stickiest hands and trickiest feet, Hernandez was the rampaging ball runner who was turned on by pain. To have either one on your team was a huge advantage; the Patriots had both.

Then in 2013, Hernandez was arrested. In April 2015, Hernandez was found guilty of the murder of Odin Lloyd, who dated his fiancée’s sister. Two years later, he was acquitted of a double slaying — just days before his suicide. Speculation abounded, but no one could ever ascertain why he killed or why he committed suicide.

Then in 2013, Hernandez was arrested. In April 2015, Hernandez was found guilty of the murder of Odin Lloyd, who dated his fiancée’s sister. Two years later, he was acquitted of a double slaying — just days before his suicide. Speculation abounded, but no one could ever ascertain why he killed or why he committed suicide.

Thomas Hodgson is better known as the tough-talking sheriff of Bristol County than as a Christian. He deprived inmates of TVs, reduced meal portions and sent out shackled prisoners to work in crews. He offered to build Trump’s wall along the Mexican border and charged his prisoners $5/day/room to help offset prison costs.

In Massachusetts where Democrats run deep, his law and order ethics resonated with many blue-collar workers and ran contrary to the elitists that ran the state. Was he politicking like Joe Arpaio, the anti-immigrant Arizona sheriff?

Maybe. But he was also genuinely concerned for the spiritual well-being of his inmates. To gasps of civil rights hounds, he ripped out equipment from the prison gym and made it into a spiritual retreat center.

Maybe. But he was also genuinely concerned for the spiritual well-being of his inmates. To gasps of civil rights hounds, he ripped out equipment from the prison gym and made it into a spiritual retreat center.

Growing up in Chevy Chase, Maryland, Hodgson was one of 13 children. He went to Catholic mass every morning at 6:00 a.m. and studied at a Catholic military high school before taking college classes in criminal justice.

The Bristol County House of Corrections in Massachusetts was under Hodgson’s administration; 41% of its population were defendants, according to the Boston Globe.

When Hernandez was brought there, Hodgson took a special interest in his high profile inmate. He spoke frequently about him publicly.

“He had the world in his hands. His destiny was set for greatness, until he made a bad decision. And suddenly, his life changed,” he sternly warned eighth graders on a field trip to the Fall River Justice Center on Law Day.

But Hodgson wasn’t just capitalizing on the footballer’s fame for self-aggrandizement. Behind the scenes, he was genuinely interested in the condition of his soul. Taking advantage of his role as maximum authority in the jail, Hodgson began to meet Hernandez privately and talk to him about his faith and his father, who died when he was 16.

“There’s a saying my father used to always use with my 12 brothers and sisters,” Hodgson told him. “He used to say, ‘Always remember, God writes straight with crooked lines.’”

“What does that mean?” Hernandez responded.

“That there are certain things that are going to happen, you’re not going to know why or how, but they’re going to happen. Do you read the Bible?”

“I used to. My coach in Florida used to get me into the Bible stuff.”

“Did you find it useful?”

“Yeah, I did.”

“Well, you’ve got a Bible in your cell. When you get back there, I want you to read it, and talk to your father and think about what I told you about crooked lines.”

Hernandez was constantly getting into trouble in jail. Once he punched an inmate in the head simply because he was looking at him. That inmate later explained that he stared at Hernandez only because he was a Patriot’s fan.

When Hernandez first came to jail, corrections officers were concerned for his safety. Would a hardened criminal do him violence to gain fame?

Quickly they realized they needn’t worry for Hernandez but rather because of Hernandez. In 10 months of Massachusetts’ Bristol County jail’s segregated unit, Hernandez was punished with 120 days in solitary confinement.

Hernandez would even threaten corrections officers.

Still, Hodgson thought he was making headway with the hot head.

But then Hernandez’s lawyers interposed. They wanted their defendant closer to Boston so they could consult with him more readily, and they didn’t like the growing relationship between Hernandez and Hodgson, whom they suspected of working for the district attorney.

Tragically the evangelization was cut short, but was a mustard seed of faith sowed in his heart?

Aaron Hernandez grew up in Bristol County. He was a star on the high school football team. His dad would watch all his games, crying, but he instilled in his son toughness and told him never to cry. During a routine hernia operation, his father unexpectedly died when Hernandez was 16.

Aaron Hernandez grew up in Bristol County. He was a star on the high school football team. His dad would watch all his games, crying, but he instilled in his son toughness and told him never to cry. During a routine hernia operation, his father unexpectedly died when Hernandez was 16.

“He was very, very angry,” his mother, Terri Hernandez, told USA Today in 2009. “He wasn’t the same kid, the way he spoke to me. The shock of losing his dad, there was so much anger.”

He became fascinated with guns and began using drugs — marijuana, cocaine and PCP, according to author James Patterson, who also said the young star was becoming “psychopathic.” He loaded up his arms and chest with tattoos. One said, “God forgives,” written backwards so as to be readable in the mirror.

Despite the troubling turn, he still played exhilarating football and was recruited in 2007 for the University of Florida’s winning program under devout Catholic Urban Meyer in 2007-09, which led to a national championship.

Coach Meyer was aware of Hernandez’s volatility — once he punched a bar attendant so hard he ruptured his ear drum. Coach Meyer tried to manage Hernandez’s outbursts with spiritual talks. He even asked his Christian quarterback, Tim Tebow, to room with Hernandez so as to be a good influence on him.

Coach Meyer was aware of Hernandez’s volatility — once he punched a bar attendant so hard he ruptured his ear drum. Coach Meyer tried to manage Hernandez’s outbursts with spiritual talks. He even asked his Christian quarterback, Tim Tebow, to room with Hernandez so as to be a good influence on him.

But as problematic as Hernandez was, his old coach never expected him to resort to such crimes.

“You hear stories about the fall from grace,” Meyer said to CBS. “And this might be one of the most tragic of all time.”

After three stellar seasons and being named an All-American his junior year, Hernandez opted for the NFL draft and was picked up in 2010 by the New England Patriots, along with Gronkowski. He racked up some of the NFL’s most impressive statistics in four seasons.

He bought a mansion for his fiancee, Shayanna Jenkins in 2007, with whom he had a daughter, Avielle Janelle Jenkins-Hernandez, in 2012.

Then he was arrested.

Overnight, he went from legend to loser, from golden boy to jailbird. The Patriots quickly released him, dissolved his contract, and distanced themselves from their former star.

He was convicted for the murder of Odin Lloyd but was later acquitted for the double slaying in 2012 outside of a Boston nightclub of Safiro Furtado and Daniel de Abreu. He had an appeal pending on the conviction. Still, five days after his acquittal, Hernandez hung himself.

Speculation abounded as to why he committed suicide. Was he trying to clear his record through a Massachusetts law that exonerates defendants who die before their trial is complete? Did he, facing life behind bars, have nothing left to live for?

Was he trying to send a spiritual message to the world by painting John 3:16 on his cell with his own blood?

In September 2017, researchers at Boston University’s CTE Center concluded that Hernandez had brain injuries at the time of his death consistent with stage three CTE (on a scale of four), the New York Times reported.

The statement noted “CTE is associated with aggressiveness, explosiveness, impulsivity, depression, memory loss and other cognitive changes.” In interviews the neuropathologist called Hernandez’s brain a classic case of the disease.

Whether the disease factored into his murder of Lloyd, his future brother-in-law, will remain a mystery.

But even more perplexing is this gnawing question: What is Hernandez’s eternal address?

Brian Bolt, a professor at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich., is optimistic. As co-chair of Sport and Christianity, a group of Christian coaches, administrators and theologians, Bolt has an eye and heart for the vagaries of professional athletes, their struggles and their encounters with Christ.

“Aaron Hernandez, through his struggles,” he told the Washington Post, “either came to Christ, or was already there and was feeling remorse.”

If you want to know more about a personal relationship with God, go here

Michael Ashcraft teaches journalism at the Lighthouse Christian Academy in Santa Monica.

Comments are closed.