By Brian Stanley —

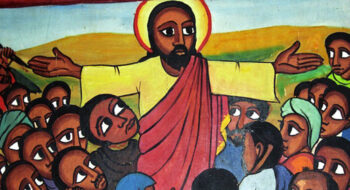

- Christianity is a western religion.

It neither began in western Europe, nor has it ever been entirely confined to western Europe. The period in which it appeared to be indissolubly linked to western European identity was a relatively short one, lasting from the early sixteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries. The Church in China, India, Ethiopia, and Iraq is older than the Church in much of northern Europe.

- Christian missions operated hand-in-glove with the colonial powers.

Sometimes they did, but frequently they didn’t. Missions were usually critical of the way in which empires operated, mainly because they conceived of empire as a divinely-bestowed trust. True, they didn’t oppose colonial rule on principle, but then who did before the late 20th century?

- Christianity was imposed by force on non-western people.

If this were true, it would reduce non-western Christians – even today – to the status of passive recipients of western ideological domination. In fact western missions never possessed the power necessary to achieve such capitulation, even if they wanted it, which they did not.

- Protestant missions began with William Carey in 1792.

John Eliot’s mission work among the Native Americans of New England began as early as 1646. The first Lutheran missionaries arrived at Tranquebar in South India in 1706. In his famous Enquiry (1792) Carey was insistent that he had many predecessors.

- Missionaries destroyed indigenous cultures.

Indigenous cultures were not static entities: to suggest that they were is characteristic of western modernity. Missionaries often displayed what we would term cultural blindness, but their message, once translated into the vernacular, acquired indigenous cultural overtones. Missionary contributions to the inscription and study of indigenous languages have helped to preserve or enrich such cultures.

- The nineteenth century was the great century of Christian missions.

It was the great age of western missionary expansion, but not the great age of indigenous conversion and agency: that was the twentieth century. K. S. Latourette’s ‘great century’ is a misleading phrase.

- ‘Christianity, Commerce, and Civilization’ was an imperial creed.

It was essentially an anti-slavery humanitarian creed, associated especially with David Livingstone (though he didn’t invent it). For those reasons it often led to advocacy of imperial solutions. Anti-slavery was a great driver of imperial expansion in Africa.

- We live in a post-missionary era.

No, we don’t. There are approximately 426,000 foreign missionaries in the world today. In 1900 there were about 62,000. The USA still sends something like 127,000 missionaries overseas.

- We live in a post-colonial age.

We certainly don’t live in a post-imperial age. Formal colonial rule is usually a last resort adopted by powerful nations who run out of cheaper options of control. Decolonisation can be seen as a return to informal means of control. Definitions of what constitutes colonialism are contested: what about the subject status of First Nations people in Canada, aborigines in Australia, Tibetans, West Papuans … and even the Scots?!

- To proclaim the unique saving value of the Christian gospel is to be intolerant of other religions.

This is to confuse a theological position with an attitudinal stance. Because of their understanding of the nature of truth, Christians can (should?) believe that others are fundamentally mistaken in their beliefs and still defend to the hilt their right to hold and practise such beliefs.

Brian Stanley read history at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and stayed on in Cambridge for his PhD on the place of missionary enthusiasm in Victorian religion. He has taught in theological colleges and universities in London, Bristol, and Cambridge, and from 1996 to 2001 was Director of the Currents in World Christianity Project in the University of Cambridge. He was a Fellow of St Edmund’s Collge, Cambridge, from 1996 to 2008, and joined the University of Edinburgh in January 2009.