By Brian Nixon —

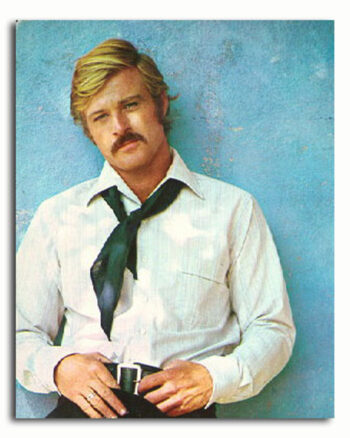

Editor’s note: With the passing of actor Robert Redford, God Reports is republishing an edited version of Brian’s earlier article, paying tribute to the life and work of an American original.

_______________________________

The year 1969 holds a peculiar weight for me. It was the year N. Scott Momaday won the Pulitzer Prize for House Made of Dawn and the year Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid vaulted Robert Redford into Hollywood’s firmament. It also happens to be the year I was born—far less momentous, of course, but enough to tether me to that remarkable moment in cultural history.

Like many children growing up in the 1970s, I knew Robert Redford as a constant presence—onscreen, behind the camera, and in the wider world of celebrity. For a time, he seemed ubiquitous. Between 1974 and 1976, Redford reigned as Hollywood’s top box-office draw. Yet the decade also revealed the breadth of his passions: environmental causes, Native American rights, and a persistent refusal to be confined to the role of mere movie star. Fast-forward to 2014, when Time magazine named him among the world’s most influential people, and the arc of his influence is clear. Robert Redford is, simply, a legend.

Momaday, by contrast, entered my awareness more slowly. Though we both grew up in New Mexico, his name was a faint echo in my junior high years, overshadowed by more familiar figures like Tony Hillerman. Only in college did I begin to appreciate his work. Since then, I’ve come to hold deep respect for his vision, particularly as the first—and still only—Native American writer to receive the Pulitzer Prize in literature.

So, when I learned that Redford and Momaday would share a stage in Santa Fe to discuss the state of the earth, my attendance was inevitable.

The evening unfolded in the St. Francis Auditorium, its walls adorned with murals by Carlos Vieira. The atmosphere carried both gravity and intimacy, as the two men began their dialogue. Act one took the form of a scripted exchange, first performed at Carnegie Hall, in which Momaday emphasized the sacredness of the earth and the moral imperative to guard it against ruin. The message was plain: in protecting the earth, we protect ourselves.

Act two opened into conversation. Guided by Jill Momaday, daughter of the author, the discussion drew us into the personal realms of Redford and Momaday—their creative beginnings, their reverence for nature. Redford spoke of Yosemite, where he worked summers after a bout with polio: “I don’t want to just look at nature,” he said. “I want to be in it.” Momaday recalled moments in New Mexico that left him awestruck at creation’s grandeur. Asked about artistic inspiration, Redford credited a teacher who taught him that “art is essential.” Momaday pointed to his parents—his mother a writer, his father an artist—and to his enduring love of poetry, especially Wallace Stevens. For him, all stories are variations on one primordial quest, the great narrative from which others descend.

When the talk turned practical—what can be done to counter the earth’s degradation—their answers carried the weight of experience. Redford urged restraint in our surrender to technology, insisting that true respect grows only from lived encounter with nature. Momaday named pollution the planet’s most insidious threat: plastics choking the seas, smog cloaking the skies. Both men spoke with urgency, yet also with hope.

Their words lingered with me as a Christian, stirring the question: What is my responsibility in caring for God’s creation? For guidance, I returned to Francis Schaeffer’s Pollution and the Death of Man. Schaeffer insists that nature is neither to be worshiped nor dismissed but cherished as God’s gift, imbued with intrinsic worth because God made it. Stewardship, in his view, is inseparable from faithfulness. To tend creation is to honor the Creator.

The Christian hope does not rest on nature itself but on Christ, whose kingdom is unfolding “on earth as it is in heaven.” Yet within that hope lies the call to labor alongside him, restoring what God declared “good.” Revelation promises a new heaven and earth, but until that day we are stewards of the present one.

In this, the Christian’s charge converges with that of environmentalists like Redford and Momaday: care, reverence, protection. For in the beginning, God pronounced creation good. That should be enough for us. And so, I find gratitude for voices like theirs—voices that keep the earth in conversation. May we have the ears, and the will, to listen.