By Brian Nixon —

Recently I had a phone call with a retired minister within the Church of the Brethren, Marilyn Lerch. A couple of years after her retirement, she discovered German Fractur art made by Christian immigrants who brought this unique form of art to the New World, writing about her findings in Messenger magazine.

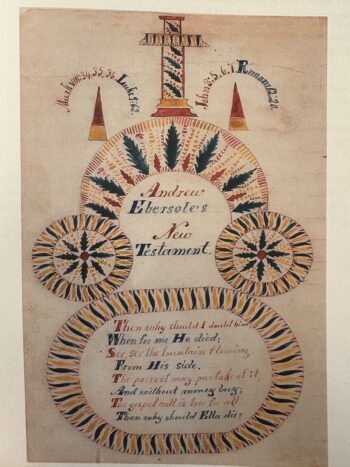

In her article Uncovering Brethren Fractur, Lerch described Fractur art as “artistic documents, mostly created with colorful paintings of birds, hearts, flowers, angels, religious characters, and symbols. The text is distinctively written with ‘broken’ letters—more like printing than cursive writing. These documents contain family information as well as passages of scripture, often offering words of wisdom, blessing, and encouragement” (Messenger, October 2023).

Around the time of Lerch’s discovery of the wonderful world of Fractur, I spent a considerable amount of time researching and reading about this overlooked form of artistic expression, particularly Douglas Shelly’s book The Fraktur-Writings or Illuminated Manuscripts of the Pennsylvania Germans. I published an essay in Bethany Seminary’s Brethren Life & Thought highlighting the Ephrata Cloister’s use of Fractur entitled Eyes to See: Toward a Brethren Aesthetic.

Often described as illuminated folk art, Fractur has deeper, spiritual connotations with many German Christian populations: Mennonite, Brethren, German Reformed, Schwenkfelders, and Lutheran. In a nutshell, Fractur art is illustrative art, first created in the New World in Pennsylvania, but its history goes back to various regions in medieval Germany, Alsace and the Rhineland areas as particular note.

Using ink and watercolor, Fractur was used in various environments: educational, religious, and commemorative (marriage and birth certificates). The practice continues into the 21st Century in some communities.

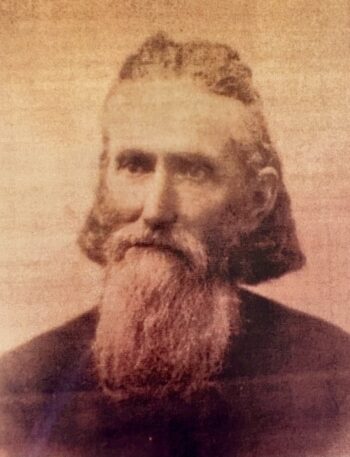

Of the people Lerch discovered in her research, one stood out for her: Christian Hervey Balsbaugh (1831-1909).

Described by Google’s AI as an “American artist, specifically known for Fraktur art, a style of illuminated manuscripts popular among German-speaking Protestants in the United States. He created these pieces, often for Brethren churches along Swatara Creek in Pennsylvania, during the mid-1800s to early 1900s. His work includes birth records, Bible records, and other examples of Fraktur.”

Lerch told me that Balsbaugh was as much a theologian as an artist, using his long bouts with illness to write letters to people, answering Bible and theological questions, in addition to creating art.

As one interested in theology and art, I was intrigued.

Brethren author, D.L. Miller, writes about Balsbaugh in his book Some Who Led. In the book we learn that Balsbaugh “had insatiable desire for learning,” studying by the dim light until his eyes “felt like crackling.”

“He taught school at the age of nineteen and spent what he earned to get further training in the Harrisburg Academy. He taught again and then went to school at Gettysburg. Here he became very ill, and after a time taught again and then attended the Freeland Seminary in Montgomery County, Pa. While here he was baptized by Brother George Price, June 13, 1852. He again resumed teaching, but health failing he turned his attention to the study of medicine…”

After various sicknesses, Balsbaugh turned to art and writing.

Miller continues: “He had always by inclination and discipline he loved the pen. He says, ‘Many of my articles were written while I was lying on my back with a board or some other support across my knees.’ His physical condition and the activity of his mind led him to study, meditation and writing.”

Miller quotes Balsbaugh, “Through all these years of pain and loneliness God was training me in deeper self-knowledge.”

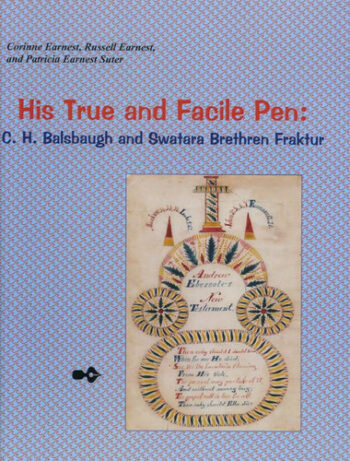

Marilyn Lerch mentioned to me that a book was written about Balsbaugh’s artwork, His True and Facile Pen, written by Particia Earnest-Suter, Corinne Earnest, and Russell Earnest.

To get more insight on C.H. Balsbaugh, I reach out to Patricia Earnest-Suter about this fascinating man of American history.

Can you give us a brief overview Balsbaugh’s life?

Christian-Hervey Balsbaugh (C.H. Balsbaugh) was born in 1831 in Dauphin County, PA. He married Hariet Gipe and then, after her death, Harriet Shelly. Balsbaugh died in 1909. He was quite intelligent, but his health was poor, which I suspect shaped his life.

As we mention in our book His True and Facile Pen, Brethren are close cousins to Mennonites. Brethren first arrived in Philadelphia in 1719, settling in Germantown. In 1729, the founder, Alexander Mack, arrived with others, helping to establish several churches.

In addition to his artwork, Balsbaugh wrote letters, a spiritual confidant to many people. Do we know what he wrote about?

The Brethren adhere closely to the New Testament. Many of his letters would reflect Biblical values. As we note in our book, “Balsbaugh carried on a significant ‘ministry of the pen’…He wrote inspiring missives of instruction and encouragement…that soar to great heights.” His letters traveled the world. Long before social media, it’s impressive to think how broad his communication travelled without the benefit of a typewriter or a ball-point pen.

Balsbaugh published his autobiography–Glimpses of Jesus or Letters of C.H. Balsbaugh Containing Also His Autobiography in 1895.

Furthermore, as we note in our book, Balsbaugh was part of the Big Swatara region (southeastern Pennsylvania), largely populated by German Brethren. Because Brethren do not practice infant baptism (no child baptism records), Balsbaugh’s Fractur art and letters would reflect the theology of his denomination, which would include Biblical texts, marriage certificates, watercolor drawings, and nature.

Balsbaugh’s work came after the heyday of Fractur art in America (before the printing press became the preferred method of creating documents), why do you think someone—like Balsbaugh—continued to create unique works of art to express his or her faith?

Once they settled in the New World, Fractur became an American form of art, one of the earliest genres. It can be argued that it is among the earliest forms of American art.

Once they settled in the New World, Fractur became an American form of art, one of the earliest genres. It can be argued that it is among the earliest forms of American art.

As he was unhealthy and often bedridden, I think Balsbaugh found it a beautiful way to express himself, to connect to people, and make a little money while doing so.

Overall, it was a manifestation of his faith.

To learn more about Balsbaugh, go to the Earnest Archives and Library or read about him in D.L Miller’s book, Some Who Led (page 157).