By G. Wright Doyle —

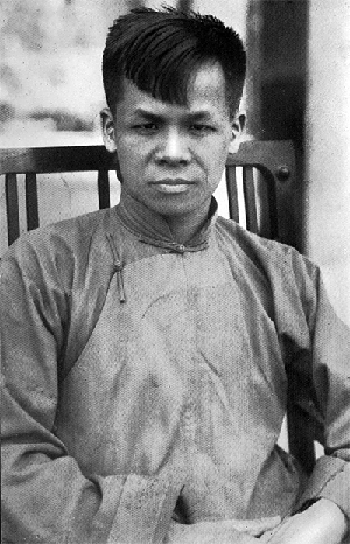

John Sung was born in Fujian Province in 1901, the sixth child and fourth son of Sung Xue Lian, a Methodist pastor.

Sung’s father was idolized and imitated by the young boy, who himself was known as “little pastor” because he accompanied his father and even preached to his classmates.

After primary and secondary education in mission schools, he was sent to America to study the Bible and theology in preparation for Christian ministry in China.

When he arrived in the U.S., he chose to study chemistry instead, enrolling in Ohio Wesleyan University. After graduating, he entered Ohio State University, from which he earned a Master’s degree in Chemistry and a Ph.D. in 1926, winning high academic honors all along the way.

Although he briefly held a position as assistant professor of chemistry, in 1926 he honored his early commitment to study theology and entered Union Theological Seminary in New York. He was at first influenced by his theologically liberal teachers, but everything changed – again, according to his testimony – when he underwent a dramatic conversion while attending evangelistic meetings in January, 1927.

He was born again on February 10th of that year.

Fully transformed, Sung zealously evangelized his professors, warning them of eternal punishment if they did not repent. They were not amused, and had him locked up in an insane asylum, where he proceeded to read the Bible through at least 40 times in seven months, according to Sung and his biographers.

Archival materials from Union Theological Seminary, paint a different picture. Those materials state that Sung suffered a psychological breakdown, leading to hallucinations, strange dreams, visions, and bizarre behavior, including impenetrable letters and diagrams.

Archival materials from Union Theological Seminary, paint a different picture. Those materials state that Sung suffered a psychological breakdown, leading to hallucinations, strange dreams, visions, and bizarre behavior, including impenetrable letters and diagrams.

The Seminary’s position is that he was diagnosed as psychotic by three psychiatrists and he signed the self-admittance form to Bloomingdale Hospital in White Plains, New York. While in the hospital, he expressed a desire to return to Union, but was rebuffed by the president, Henry Sloan Coffin, because the seminary had already spent a large sum of money for his hospital stay and feared further mental instability.

Sung was released from the asylum through the efforts of an American pastor and returned to China in 1927.

He married Yu Jin Hua (“Jean”) shortly after his return. The marriage was arranged by his parents, and entered into only with reluctance and reservations, but he sought to bring his wife to faith in Christ. Together they had three girls and two boys, who were all given biblical names.

Initially, Sung taught at Methodist Christian High School in Fujian to help put his younger brother through college, engaging in evangelism on the weekends, but resigned after one year.

Meanwhile, the Nationalist Party became unhappy with him for refusing to have his students bow to the picture of Sun Yat-sen, and initiated a campaign of rumors, threats, and opposition that lasted for the rest of his ministry, even though he always taught that Christians must obey the government.

He joined up with an evangelistic band and traveled around the province, preaching and teaching in small, rural churches for three years, at the request of the Methodist Bishop of the region.

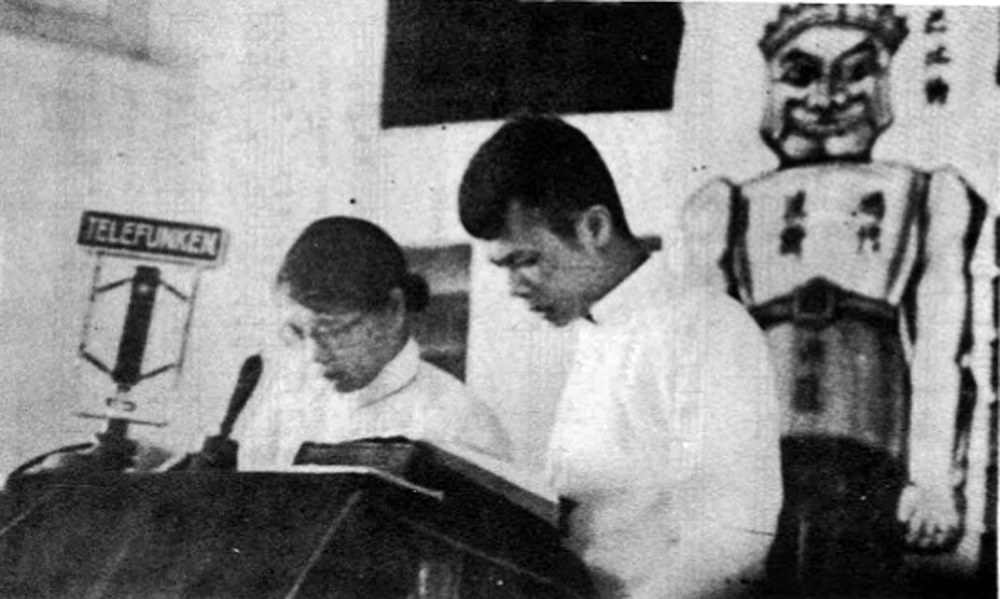

In 1931 he was invited to become a member of the Bethel Worldwide Evangelistic Band, traveling throughout northeastern, northern, and southern China. During their first year together, the band preached to more than 400,000 people.

He was told to leave the band in 1933. He claims that the leaders in Shanghai wrongly suspected him of diverting funds to his own use and intending to set up an independent ministry, but he had become the leading “star” of the group and it might have been just a matter of time before his ministry needed to separate from theirs. He then decided to become a fully independent itinerant revivalist and evangelist.

For the next eight years, he tirelessly traversed the roads and rails of China, and made five epic journeys (1935-1940) to Southeast Asia, including Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Indonesia, as well as the Japanese-occupied island of Taiwan.

Preaching in large churches and small, in major cities and rural villages, he attracted huge crowds, many thousands of whom were deeply moved by his preaching, and responded with weeping, open confession of sin, and expressions of commitment to Christ. He battled both external opposition, including slander and threats of death, and internal church division and strife, not to mention his own physical weakness and pain, but he kept pushing on, passionate in his desire to see people come to saving faith in Christ.

“China’s John the Baptist”

His preaching came from the Bible, which he studied carefully, reading 11 chapters daily. He employed parables, real-life stories, and his own personal testimony as illustrations of biblical truths. Sometimes he would call for volunteers to ascend the platform, then hang placards around their necks with specific sins (“lying,” “stealing,” “adultery”) written on them.

Quite frequently, he rebuked specific wrongdoing, often pointing out or naming church leaders whose misdeeds he had learned about from their church members. He wrote that a preacher must speak on: “Repentance; Heaven and Hell, and the cross and the blood of Christ;…hating of sin and complete consecration; … being filled with the Holy Spirit; …the life of faith, as well as… love… In addition, one must live a life of hope.”

In particular, he stressed the necessity of Christians to follow in the footsteps of Christ, bearing the cross of suffering with faith and joy. The return of Christ figured largely in his preaching, as did reminders that soon all our needs would be more than fully supplied in a New Heaven and a New Earth.

To make a more lasting impact, he organized several Bible conferences, some of them lasting a full month, in which expounded the entire Bible, book by book.

lasting a full month, in which expounded the entire Bible, book by book.

An excellent actor, Sung would play the parts of the various biblical characters whose story he was telling. He paced back and forth across the stage; used “props” such as a small coffin to represent the dark mass of sin within each of us; broke into song or prayer in the midst of his sermons, and otherwise kept his audience enthralled. He composed many songs, which he would teach the congregation to sing with him.

Everywhere he went, Sung sought earnestly to promote church unity. He attacked abuse by leaders; exhorted members to forgive and love each other; and taught them how to follow the meekness of Christ in their relationships with each other.

Healing Ministry

Beginning in December, 1931, Sung exercised a truly stunning ministry of physical healing through prayer. Thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of people were delivered from all sorts of illnesses, infirmities, and addictions after he prayed for them. These miracles were witnessed by countless people, many of them originally skeptical of this aspect of John Song’s ministry.

Opium addicts received instant delivery. Smokers kicked the habit “cold-turkey.” Those possessed by evil spirits were delivered. Blind people received their sight; the lame walked; disabled limbs were healed; leprosy cured instantly.

Sung did not, however, give precedence to physical well-being. At each meeting, he first preached a sermon on the need to repent and to trust fully in Christ for salvation, insisting that full repentance of sins must precede lasting healing. Nor did he emphasize spiritual gifts, but stressed faith in Christ and holiness of life.

Relationships with foreign missionaries

Sung was wary of domineering foreign missionaries. In his diaries, he criticized those who opposed his ministry because they were either envious or ignorant of his message; those who lived comfortably, even luxuriously, in the midst of poverty and suffering; those who looked down on their Chinese co-workers; and especially those with liberal theological views.

His experience at Union Theological Seminary had thoroughly disillusioned Sung, even as it alerted him to the fundamental differences between liberalism and traditional biblical Christianity.

On the other hand, when he came across self-denying, humble missionaries, he commended them freely. Sometimes their willingness to live among the Chinese, eating and dressing like the locals, and serving faithfully for many years, greatly moved him. He gladly welcomed the cooperation of foreigners in his revival and evangelistic efforts, and rejoiced when some of them openly repented of their unbelief and sin.

Personal life

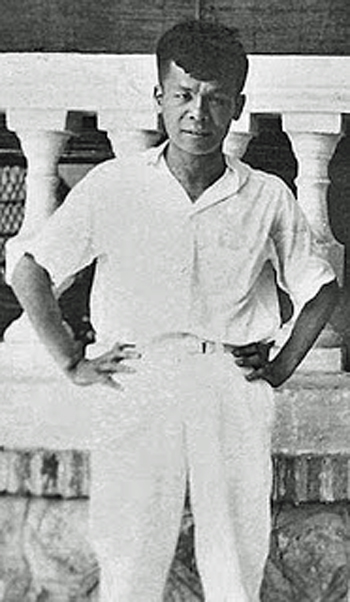

Sung shared the perilous conditions of his fellow citizens. He did not shrink from traveling into combat zones, or preaching with enemy planes flying overhead. In the midst of extreme poverty, he himself lived simply, even ascetically.

He insisted upon traveling third class on the train, when he could have afforded better seating. When given money for travel expenses, he typically returned it, or donated most of the funds to someone in greater need.

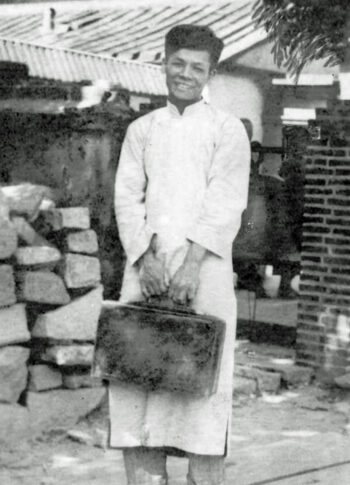

Wearing a plain Chinese-style scholar’s gown and carrying a tattered leather briefcase, he stayed wherever he found a welcome or a place to rest, no matter how uncomfortable.

The abscesses which he acquired while studying in America flared up whenever he taxed his body too much, which was often. This “thorn,” as he called it, caused him indescribable pain, sometimes forcing him to preach sitting down or even lying on a bed on the platform. He was aware that his own bodily frailty helped to curb his pride and remind him of his sins, especially his short temper.

At various points in his life, and especially towards the end, he realized that he had neglected his family, being gone from home 11 months of the year, including each time his wife gave birth. For the last three years of his life, as he recuperated from six different surgeries outside of Beijing, he exhorted others to spend more time in prayer, believing that he had relied too much on his own strength and not enough upon God.

Sung’s distinctives included his confrontational style and ruthless denunciation of sins and of liberal theology; a willingness to confess and ask forgiveness publicly for losing his temper; effective prayer for healing; a unique combination of a simple faith with intellectual brilliance; the organization of evangelistic bands; unusual skill as a dramatic communicator in a variety of media, including song and the written word; and the huge numbers of people who were affected by him.

Perhaps as many as 100,000 were lastingly converted through his ministry, which would amount to one-tenth of Protestant Christians in China. His work and that of others like him laid the foundation for the remarkable resurgence of evangelical, revivalist Christianity in China in the last part of the twentieth century.

The discrepancies between his narrative of what happened at Union Seminary and historical fact, seem to accord with his dramatic personality. They do not discredit his later ministry, but cast light upon a complex figure whose lasting legacy remains immense.

G. Wright Doyle is the director of the Global China Center; English Editor, Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA. (Edited by Mark Ellis) The full article appears in the Biographical Dictionary of CHINESE Christianity here